ACOSTA: Well, I was invited by a friend of mine who used to be a missionary in Colombia and live in that area. Yeah, it's north of Birmingham [Alabama]. It's...it's a...it's a county. And he...he's been trying to do some work with these migrants and...because he knows Spanish and he...he just loves Latin America and wants to do something with these people. So he called me on the telephone and asked me if I wanted to go there and spend a summer, and they would provide a house and food and everything for me. So I was...I was actually praying for an opportunity to do some kind of ministry at the time he called. So I said, "Yes," [laughs] because I wanted to do some...something like that.

INTERVIEWER: What did he have in mind for you to do?

ACOSTA: Well, he...I didn't have the...the title of pastor, but in a way, I was like a...well, lay pastor or whatever. That was the kind of work I was doing. So he wanted me to go and teach, like lead a Bible study and preach on Sundays and also try to minister to the needs of the people like some kind of social work. And also the idea was like to be a link between the American community and migrant workers.

INTERVIEWER: Now what...what was the ethnic background of most of...of the people you were working with?

ACOSTA: Majority of them were Mexicans, and there were a few from other countries in Central America. But, basically Mexican people, and people who come from...they are...most of them are farmers in their countries. They come from...they call it a rancho. It's a small...very small town where they know everybody, and they...they...they do agriculture and that's...that's the kind of people that I was working with.

INTERVIEWER: Now what...what kind of crops were they working with in Alabama? What was the main...?

ACOSTA: Well, most...most of them were picking tomatoes. And there...there were also watermelons, cucumbers, peaches, and onions, squash, and a few other things. But the big thing is tomatoes, all different kinds of tomatoes. And there is especially one guy in that area where I was that has a large farm, and he's the one that hires a lot of people.

INTERVIEWER: Now would these...were the same migrant workers there the entire summer that you were there?

ACOSTA: Well...well, they...they come in the spring. They start coming in the spring.

INTERVIEWER: And where would they come from?

ACOSTA: Well, some of them came from Florida or Georgia or somewhere around Texas. But I would say that most of them came from Mexico, straight from Mexico, at least the people I wa...I came in contact with. And they...they come in the spring, and they...I...I just talked to a friend of mine, (the friend who called me to go there last night), I talked to him and he said that most of them are still there. So it's six, seven months.

INTERVIEWER: And then, when the season is over, what do they do?

ACOSTA: Well, they either go back to Florida if they came from Florida [laughs], or they go back to Texas if they came from...or back to Mexico. Most of them in this area go back to Mexico. Now there are few families that have settled in the area. So they...they live in Alabama. They don't go back. If they go back to Mexico, it would be for visit, but not to stay in Mexico.

INTERVIEWER: Now what's the legal status of these folks?

ACOSTA: [laughs] Well, I was...I didn't know when I first got there, and I was a little bit surprised in a way and didn't understand why some guys would not tell me their names. Like I talked to a couple of guys one time, and I told them my name, and I asked them what their names were, and they said well, that's not the most important thing [laughs]. And I talked to the person who was with me and said, well, maybe they think you're from the immigration office or something. So there are a few who are not...who don't have any documents whatsoever, nothing, nothing at all. I met a g...I met a guy from Guatemala, and he didn't have any document at all, not even from his own country, nothing. And...but most of them are legally in the country. They have a...a special document that allows them to work for one or...either one or two years. And they have to...when that...that expires they have to go to Atlanta, Georgia, and get a new one. So most of them, I would say, are legally in the country.

INTERVIEWER: How did you find that you related to the workers, being a Latin American too?

ACOSTA: [coughs] Well, I find out that we were more different [laughs] than I thought we would be.

INTERVIEWER: How so?

ACOSTA: Well, in a way because I am fro...I am Latin America...from Latin America, but I am from the cities, and these guys are not from city. So...and the other thing is that I'm used to working with university students, and these people...they...they can barely write their names, a lot of them. So, it was a very, very interesting experience for me because, you know, I had...when I went down there I had a program in my mind, you know, like a structure of the things I wanted to do. But I had to put that aside and do something new, something different.

INTERVIEWER: How quickly did you realize that?

ACOSTA: Oh, the first week [interviewer laughs] The first week because they...they don't have a schedule. That's one thing, so you cannot have a, you know, like a calendar of things you want to do in the future because usually when we wanted to do something we would plan it the night before [laughs] the next day. So, one thing that was definite that really helped me to get closer to them was to go and work with them, picking tomatoes. Now that was hard [laughs]. That's the hardest work I've ever done. Well, I've been...I've spent most of my life studying, but it's a different kind of hardness. But these...these people work eight, ten hours under the sun, and they don't eat because they are paid by the bucket so if they stop to eat they don't earn anything, so they have to just keep going. And...but that...in that context, I just worked with them for four days because that was all I [laughs] could stand. But that really opened the doors to...to really know them and to get close to them. And also inviting myself to their houses. It's like, I wouldn't expect them to say, "Why don't you come over and eat with us?" I would plan on purpose to go there at a time I suspected they would be eating. Because, you know, when...I...I believe that when you eat with people, in a way they...they...they feel accepted. And also because sometimes if they say, "Oh, this guy comes from this school," even though they don't know what school it is or what it means, but they..."This guy knows something. He's more educated than we are, so we have to respect them. So, we cannot offer the kind of food we...we have to make something special if we...we're going to ask him to come eat with us." So, I just went. And [laughs]...and now a Latin thing is that if you go there and it's about time to eat, they will invite you for sure. And so they...they invited me to eat, and...and I ate with them. It was a family, and there were some other guys living with them there too. And it was great because it started open, more and more, themself, their whole lives to myself. And...and actually we...we became good friends. I became good friends with some..some of them.

INTERVIEWER: Can you describe what the...their living conditions were like? You talk about going to their house.

ACOSTA: Well, this might be the only family that I would say that have a house [Ericksen laughs]. You know, they...now the house is not in very good condition. It's an old house, and it's...well it's...it...it meets the re...legal requirements [laughs]. Let's put it that way. But it's...it's just...you know, just the basic things. Most of them...now I have to say, most of the people that I met live in trailer homes. I was really amazed to see the conditions in which some of them live. There were in a...in a one bedroom trailer home, there were twenty-three men living there.

INTERVIEWER: Wow.

ACOSTA: And no air conditioning whatsoever, and you know Alabama's hot in the wi...in the summer. And no beds, no chairs, no tables, nothing. All they...they...they sleep all lined up on the floor, everywhere in the...in a trailer home. Now that's...that is the worst. That's one case. It's not all of them like that. But there are other trailer homes like one bedroom and ten men. That was good [laughs]. That's better than...but there were other with like twelve, fifteen. In another one there would be five or seven. You know, all of them sleeping on the floor because they...that's the cheapest housing they can find and the only way...you know, living in those conditions is the only way they can save money to send to their families back in Mexico. So, they cannot buy beds or chairs or tables, or anything because they cannot take those things back with them. And they're...and...and even if they could, they...probably they don't need them, you know. So they have to live in those conditions so that they can save money and send some to their families. So....

INTERVIEWER: It sounds like the population's predominantly male. Is that...?

ACOSTA: Yes, yes that's true. And I would say most of them married and with children too. So they come and they leave their families, and it's...it's very hard. You know, for my...I would say, you know, from my point of view, it's not worth the trouble. But they say they still do better than they would in Mexico. So they say it's worth it. So they come and...and do it, and it's a sacrifice, but they...they say they are used to that. They...it's not...they don't say it's easy. They say, "This is hard, but we are...we can handle it." And on the other hand they say, "We have to handle it because we don't have other choice." You know, if you...if you know how to...if you can do something because you have some education you have a choice in a way, but they say, "We don't have a choice. We don't know...we...we cannot do anything else." So....

INTERVIEWER: Do any of them bring...any of them bring fam...their families with them?

ACOSTA: Some, some do, but just a few. The majority of them are there without family.

INTERVIEWER: If they bring their family, what does their family do during the day, work with them?

ACOSTA: Yes. I saw children from seven...seven-year-old children up working. And they work the same number of hours their parents do, like eight, ten hours, the whole day. They take them to the fields and work with them. Ten year old, twelve, thirteen, all of them work.

INTERVIEWER: What do they tend to do with their free time?

ACOSTA: Well, that's a problem for them because [laughs] all they see is men and tomatoes. You know, [laughs] every day, all day long the same thing. You know, they wor...go to work and they see men and tomatoes. They come home, and they see men, that's all. And some of them would have a little TV set, but they do not understand English. So they...if they listen to the radio they...they do not understand anything either. So it's common to see, you know, their cars with the doors open and Mexican music playing, sso that's one thing. Or a few of them I saw would get tapes and watch a movie, Mexican movie. But, because of these conditions, and now I'm not justifying it by any means...but, because of the whole situation they...they drink...let's say more than they should, and...and they get in trouble because they drink and drive. Now the county where I was working is a dry county [laughs], but they just go across the border [laughs] and get whatever they want to get and drink and get in trouble with...because of that. So, one...one other thing that I did was go to jail and see...whether there was any Mexican. Usually there was somebody there, at least one or two. And, because of that they would spend twenty-five, thirty-seven days, and...or pay, I think, a five-hundred dollar fine, and get out. So, recreation is very poor for them. That's one thing I was trying to do with these guys, with these people. We organized what we call a Hispanic day in a Baptist camp. So the...you know, like have a day in the...the swimming pool, playing, volleyball, and eating, and talking. And also tried to plan some...some time to play sports with them. And there was a family, American family in particular, who had a big house with a swimming pool and big yard, so they...they made the house available for us, for all the Mexicans and for myself any time I wan...I wanted to bring them. So, it was really...it really worked well. They loved it. For...for some of them, it was the first time to swim in a swimming pool...to be in a swimming pool. First time in their lives. And at the beginning, they [laughs] didn't dare to...to get in the water [laughs]. So it took them...for some of them thirty minutes, and they...finally they did.

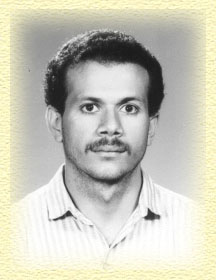

For more information about Acosta or Collection 429, click here.