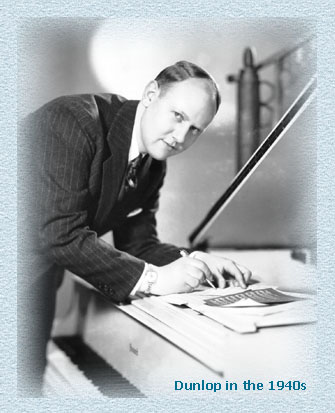

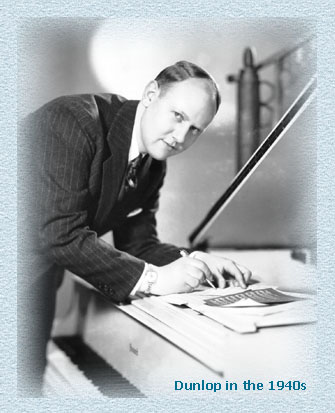

Excerpt (approximately 8 minutes) from the oral history with Merrill Dunlop (Collection

50T1), who was interviewed by Robert Shuster in 1978. For more information about

Dunlop click here.

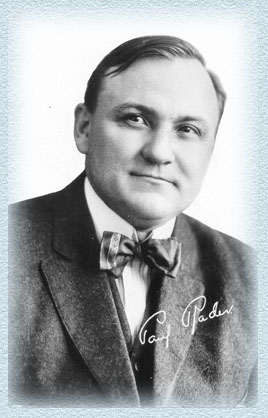

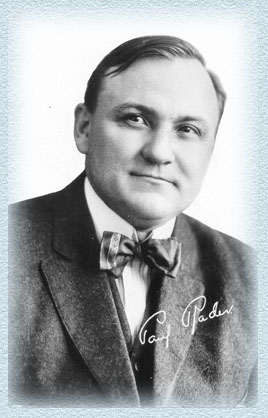

DUNLOP: And then we enlarged our music staff [clears throat] because Paul Rader went on the

air then. He was one of the first broadcasters in the city, in 1924, I think it was. He went up on

the top of the Wrigley Building to make a test on broadcasting and they had the...some horns

there. He took some of the boys and they was going to make a test for broadcasting and I just

don't know how they did it now, 'cause I...although I used to hear Paul Rader talk about that.

And this resulted in his going on the air on...on the old Chicago station WHT. Those call letters

stood for William Hale Thompson back in those days because Thompson had been the...one of

the former mayors of Chicago.

air then. He was one of the first broadcasters in the city, in 1924, I think it was. He went up on

the top of the Wrigley Building to make a test on broadcasting and they had the...some horns

there. He took some of the boys and they was going to make a test for broadcasting and I just

don't know how they did it now, 'cause I...although I used to hear Paul Rader talk about that.

And this resulted in his going on the air on...on the old Chicago station WHT. Those call letters

stood for William Hale Thompson back in those days because Thompson had been the...one of

the former mayors of Chicago.

INTERVIEWER: Big Bill Thompson.

DUNLOP: And WHT, the radio station, was located in...in the Wrigley Building. And they had

an organ down there and they...very nice studios and Paul Rader would go down there and

broadcast. And then he...they ran the...the wires out, as we call it. You know, the telephone

company's wires, of course, were engaged. And they...they set up a studio in the...in the

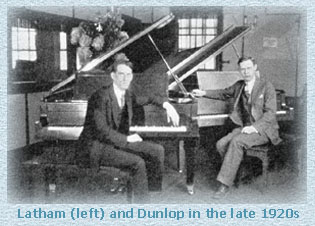

Tabernacle, Chicago Tabernacle, which was out about six miles, you see. So Lance Latham and I

would still go down to the old Wrigley Building studios for our organ recitals and we would have

earphones on and...and know what was going on back at the Tabernacle and then when they

would announce us and we'd be ready to play [laughs]. And our organ numbers would go out

that way. And sometimes we'd even do a little feat that we thought was quite wonderful in those

days. We'd have Floyd Johnson singing back at the Tabernacle and we'd accompany him at the

Wrigley Building. We could hear him over our earphones and we could put the accompaniment

on there. And, of course, the people out over listening on the radio but what it was all coming in

one place. And we did alot of interesting things that way. But, of course, later on we got a big

pipe organ in the Chicago Gospel Tabernacle. We didn't have to go down anymore to...to

broadcast. But Paul Rader changed from WHT when

[pauses].... I've forgotten the name...the

owner of the other station. I may...may think of it in a moment. But station WBBM came into

existence then and they had the studios down there  in...in the Wrigley Building. And they

enlarged the studios and it became quite a...quite a place because WBBM, of course, was one of

the big stations on the network, the Columbia network. Paul Rader wanted to get on that and so

he arranged with the owners of the station to take a broadcast on...on...on Sundays. And Paul

Rader didn't do things in a small way. He did things in a big way. And so he took...he engaged

fourteen hours, from ten o'clock in the morning on Sunday until midnight on Sunday. And so our

staff, which began to be increased in size, really had a full-time major job in...in manning the

hours of that fourteen hours on the radio. And the...the... What do they call it? The...the radio...?

The...the.... What is it? The Commerce...? I can't recall think of call letters now that control

the...the broadcasting in those days.

in...in the Wrigley Building. And they

enlarged the studios and it became quite a...quite a place because WBBM, of course, was one of

the big stations on the network, the Columbia network. Paul Rader wanted to get on that and so

he arranged with the owners of the station to take a broadcast on...on...on Sundays. And Paul

Rader didn't do things in a small way. He did things in a big way. And so he took...he engaged

fourteen hours, from ten o'clock in the morning on Sunday until midnight on Sunday. And so our

staff, which began to be increased in size, really had a full-time major job in...in manning the

hours of that fourteen hours on the radio. And the...the... What do they call it? The...the radio...?

The...the.... What is it? The Commerce...? I can't recall think of call letters now that control

the...the broadcasting in those days.

INTERVIEWER: Oh, the....

DUNLOP: Was it ICC? Not ICC. Federal Communications Commission.

INTERVIEWER: Oh, FCC.

DUNLOP: Yes. They...they wouldn't permit for some reason the use of the call letters WBBM

on Sunday. I don't remember just why that was. And so they insisted on selecting other call

letters and they assigned WJBT to...to just the Sunday use of the Tabernacle. And I remember

Paul Rader put on a sort of a little appeal to the radio people to suggest what those letters might

stand for: WJBT.

INTERVIEWER: Like a contest?

DUNLOP: Well, it wasn't exactly a contest. But "Telephone your suggestions in." You see,

they always had the switchboards open for people to call in and girls were there to take the

messages. We had a whole battery of telephones there in the office for that purpose when we

were on the air. And I remember he was asking people to suggest: WJBT. We had all kinds of

suggestions. In fact, even humor came into it. They were going to have the big prize fight down

at Soldier Field with...with Jack Dempsey and...and  Gene Tunney at that time. And some wag

phoned in and said, "WJBD...WJBT should stand for Watch Jack Beat Tunney." [both laugh]

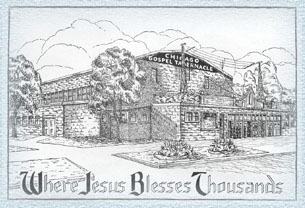

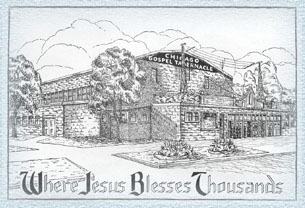

And...but anyway, the good suggestion came along, "Where Jesus Blesses Thousands." And that

was the thing that answered the question. And so that became the real big caption underneath the

name Chicago Gospel Tabernacle: Where Jesus Blesses Thousands. And the broadcasts, of

course, went on all day Sunday. And then Paul Rader wanted it to become a network deal for the

weekdays and he arranged for the morning hour from seven-thirty to eight-thirty. A full hour

every morning across the network. Well, I tell you, that really meant that we really had to get

down to brass tacks. We had a big staff then, as I said, and we broadcast the band on Sunday

nights. We broadcast the afternoon service, the three o'clock afternoon service and the seven

o'clock service at night, on Sunday night, which would take from seven until...till about

nine-thirty, I suppose, with all the music and the message and the invitation, everything.

Everything was on the radio. [clears throat] So all those other hours had to be filled in. After

the evening service, we put on what was called the "Request Hour" and people could phone in

their requests and the staff was all in the studio then. And we would do the things people wanted

us to do, the songs that were popular that day. We

had to be able to build a big hymn book

library to be able to pull the hymn books out quickly

Gene Tunney at that time. And some wag

phoned in and said, "WJBD...WJBT should stand for Watch Jack Beat Tunney." [both laugh]

And...but anyway, the good suggestion came along, "Where Jesus Blesses Thousands." And that

was the thing that answered the question. And so that became the real big caption underneath the

name Chicago Gospel Tabernacle: Where Jesus Blesses Thousands. And the broadcasts, of

course, went on all day Sunday. And then Paul Rader wanted it to become a network deal for the

weekdays and he arranged for the morning hour from seven-thirty to eight-thirty. A full hour

every morning across the network. Well, I tell you, that really meant that we really had to get

down to brass tacks. We had a big staff then, as I said, and we broadcast the band on Sunday

nights. We broadcast the afternoon service, the three o'clock afternoon service and the seven

o'clock service at night, on Sunday night, which would take from seven until...till about

nine-thirty, I suppose, with all the music and the message and the invitation, everything.

Everything was on the radio. [clears throat] So all those other hours had to be filled in. After

the evening service, we put on what was called the "Request Hour" and people could phone in

their requests and the staff was all in the studio then. And we would do the things people wanted

us to do, the songs that were popular that day. We

had to be able to build a big hymn book

library to be able to pull the hymn books out quickly  if we didn't know a song to look it up. And

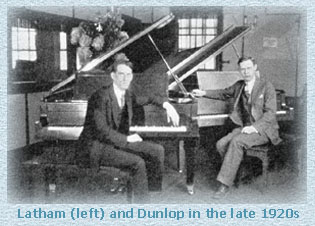

we had a whole staff of people helping us on that. Lance Latham and I were there at the pianos

and we had the brass quartet and we had James Neilson, who was a fine coronet soloist. Clifford

Benson came along and joined our staff and his..... And I can't remember all that we had. But

Paul Rader came in after that had been going on for an hour. And he came in at eleven o'clock.

From eleven to twelve we had what became famous as the Back Home Hour. Paul Rader took

his place at the desk with the microphone. (And that's shown on the Paul Rader movie which we

have.) And he took charge of that in a very masterful way. He had a great sense of humor and a

great message and he made it very informal and he'd present the staff for special numbers which

they had worked hard to prepare. You know, combinations of things. Our soloists would sing.

We'd have ensemble music, we'd have instrumental things. Lance would play, I would play. We

would use the pianos, we would go out to the auditorium and play the big pipe organ. It was just

a great time. And in those days we had no competition. We were the only ones really on the air

at that time as far as a sacred broadcast was concerned.

if we didn't know a song to look it up. And

we had a whole staff of people helping us on that. Lance Latham and I were there at the pianos

and we had the brass quartet and we had James Neilson, who was a fine coronet soloist. Clifford

Benson came along and joined our staff and his..... And I can't remember all that we had. But

Paul Rader came in after that had been going on for an hour. And he came in at eleven o'clock.

From eleven to twelve we had what became famous as the Back Home Hour. Paul Rader took

his place at the desk with the microphone. (And that's shown on the Paul Rader movie which we

have.) And he took charge of that in a very masterful way. He had a great sense of humor and a

great message and he made it very informal and he'd present the staff for special numbers which

they had worked hard to prepare. You know, combinations of things. Our soloists would sing.

We'd have ensemble music, we'd have instrumental things. Lance would play, I would play. We

would use the pianos, we would go out to the auditorium and play the big pipe organ. It was just

a great time. And in those days we had no competition. We were the only ones really on the air

at that time as far as a sacred broadcast was concerned.

INTERVIEWER: There was no other religious program of any kind?

DUNLOP: No, it was even before the wonderful programs of WMBI, which came in I think

about 1926 or '27. And...but during those early days from...from 1925, when we started to

broadcast, un...until 19...the first two or three years, we were practically on the...on the air alone

with religious broadcasting in this area.

For more information about Dunlop or Collection 50 at the Archives

click here. To read the entire transcripts of the Dunlop interviews, click here.

Continue to the next excerpt of Herbert Downing.

Last Revised: 12/20/01

Expiration: indefinite

air then. He was one of the first broadcasters in the city, in 1924, I think it was. He went up on

the top of the Wrigley Building to make a test on broadcasting and they had the...some horns

there. He took some of the boys and they was going to make a test for broadcasting and I just

don't know how they did it now, 'cause I...although I used to hear Paul Rader talk about that.

And this resulted in his going on the air on...on the old Chicago station WHT. Those call letters

stood for William Hale Thompson back in those days because Thompson had been the...one of

the former mayors of Chicago.

air then. He was one of the first broadcasters in the city, in 1924, I think it was. He went up on

the top of the Wrigley Building to make a test on broadcasting and they had the...some horns

there. He took some of the boys and they was going to make a test for broadcasting and I just

don't know how they did it now, 'cause I...although I used to hear Paul Rader talk about that.

And this resulted in his going on the air on...on the old Chicago station WHT. Those call letters

stood for William Hale Thompson back in those days because Thompson had been the...one of

the former mayors of Chicago.

in...in the Wrigley Building. And they

enlarged the studios and it became quite a...quite a place because WBBM, of course, was one of

the big stations on the network, the Columbia network. Paul Rader wanted to get on that and so

he arranged with the owners of the station to take a broadcast on...on...on Sundays. And Paul

Rader didn't do things in a small way. He did things in a big way. And so he took...he engaged

fourteen hours, from ten o'clock in the morning on Sunday until midnight on Sunday. And so our

staff, which began to be increased in size, really had a full-time major job in...in manning the

hours of that fourteen hours on the radio. And the...the... What do they call it? The...the radio...?

The...the.... What is it? The Commerce...? I can't recall think of call letters now that control

the...the broadcasting in those days.

in...in the Wrigley Building. And they

enlarged the studios and it became quite a...quite a place because WBBM, of course, was one of

the big stations on the network, the Columbia network. Paul Rader wanted to get on that and so

he arranged with the owners of the station to take a broadcast on...on...on Sundays. And Paul

Rader didn't do things in a small way. He did things in a big way. And so he took...he engaged

fourteen hours, from ten o'clock in the morning on Sunday until midnight on Sunday. And so our

staff, which began to be increased in size, really had a full-time major job in...in manning the

hours of that fourteen hours on the radio. And the...the... What do they call it? The...the radio...?

The...the.... What is it? The Commerce...? I can't recall think of call letters now that control

the...the broadcasting in those days. Gene Tunney at that time. And some wag

phoned in and said, "WJBD...WJBT should stand for Watch Jack Beat Tunney." [both laugh]

And...but anyway, the good suggestion came along, "Where Jesus Blesses Thousands." And that

was the thing that answered the question. And so that became the real big caption underneath the

name Chicago Gospel Tabernacle: Where Jesus Blesses Thousands. And the broadcasts, of

course, went on all day Sunday. And then Paul Rader wanted it to become a network deal for the

weekdays and he arranged for the morning hour from seven-thirty to eight-thirty. A full hour

every morning across the network. Well, I tell you, that really meant that we really had to get

down to brass tacks. We had a big staff then, as I said, and we broadcast the band on Sunday

nights. We broadcast the afternoon service, the three o'clock afternoon service and the seven

o'clock service at night, on Sunday night, which would take from seven until...till about

nine-thirty, I suppose, with all the music and the message and the invitation, everything.

Everything was on the radio. [clears throat] So all those other hours had to be filled in. After

the evening service, we put on what was called the "Request Hour" and people could phone in

their requests and the staff was all in the studio then. And we would do the things people wanted

us to do, the songs that were popular that day. We

had to be able to build a big hymn book

library to be able to pull the hymn books out quickly

Gene Tunney at that time. And some wag

phoned in and said, "WJBD...WJBT should stand for Watch Jack Beat Tunney." [both laugh]

And...but anyway, the good suggestion came along, "Where Jesus Blesses Thousands." And that

was the thing that answered the question. And so that became the real big caption underneath the

name Chicago Gospel Tabernacle: Where Jesus Blesses Thousands. And the broadcasts, of

course, went on all day Sunday. And then Paul Rader wanted it to become a network deal for the

weekdays and he arranged for the morning hour from seven-thirty to eight-thirty. A full hour

every morning across the network. Well, I tell you, that really meant that we really had to get

down to brass tacks. We had a big staff then, as I said, and we broadcast the band on Sunday

nights. We broadcast the afternoon service, the three o'clock afternoon service and the seven

o'clock service at night, on Sunday night, which would take from seven until...till about

nine-thirty, I suppose, with all the music and the message and the invitation, everything.

Everything was on the radio. [clears throat] So all those other hours had to be filled in. After

the evening service, we put on what was called the "Request Hour" and people could phone in

their requests and the staff was all in the studio then. And we would do the things people wanted

us to do, the songs that were popular that day. We

had to be able to build a big hymn book

library to be able to pull the hymn books out quickly  if we didn't know a song to look it up. And

we had a whole staff of people helping us on that. Lance Latham and I were there at the pianos

and we had the brass quartet and we had James Neilson, who was a fine coronet soloist. Clifford

Benson came along and joined our staff and his..... And I can't remember all that we had. But

Paul Rader came in after that had been going on for an hour. And he came in at eleven o'clock.

From eleven to twelve we had what became famous as the Back Home Hour. Paul Rader took

his place at the desk with the microphone. (And that's shown on the Paul Rader movie which we

have.) And he took charge of that in a very masterful way. He had a great sense of humor and a

great message and he made it very informal and he'd present the staff for special numbers which

they had worked hard to prepare. You know, combinations of things. Our soloists would sing.

We'd have ensemble music, we'd have instrumental things. Lance would play, I would play. We

would use the pianos, we would go out to the auditorium and play the big pipe organ. It was just

a great time. And in those days we had no competition. We were the only ones really on the air

at that time as far as a sacred broadcast was concerned.

if we didn't know a song to look it up. And

we had a whole staff of people helping us on that. Lance Latham and I were there at the pianos

and we had the brass quartet and we had James Neilson, who was a fine coronet soloist. Clifford

Benson came along and joined our staff and his..... And I can't remember all that we had. But

Paul Rader came in after that had been going on for an hour. And he came in at eleven o'clock.

From eleven to twelve we had what became famous as the Back Home Hour. Paul Rader took

his place at the desk with the microphone. (And that's shown on the Paul Rader movie which we

have.) And he took charge of that in a very masterful way. He had a great sense of humor and a

great message and he made it very informal and he'd present the staff for special numbers which

they had worked hard to prepare. You know, combinations of things. Our soloists would sing.

We'd have ensemble music, we'd have instrumental things. Lance would play, I would play. We

would use the pianos, we would go out to the auditorium and play the big pipe organ. It was just

a great time. And in those days we had no competition. We were the only ones really on the air

at that time as far as a sacred broadcast was concerned.