Treasures of Wheaton presentation, May 10, 2003

| The images below follow the sequence and location

of their use during the presentation. Links to audio files of the interview excerpts are available through the headphone icon. |

Click here to listen to the 11-minute continuous

compilation of the featured Perkins interview excerpts |

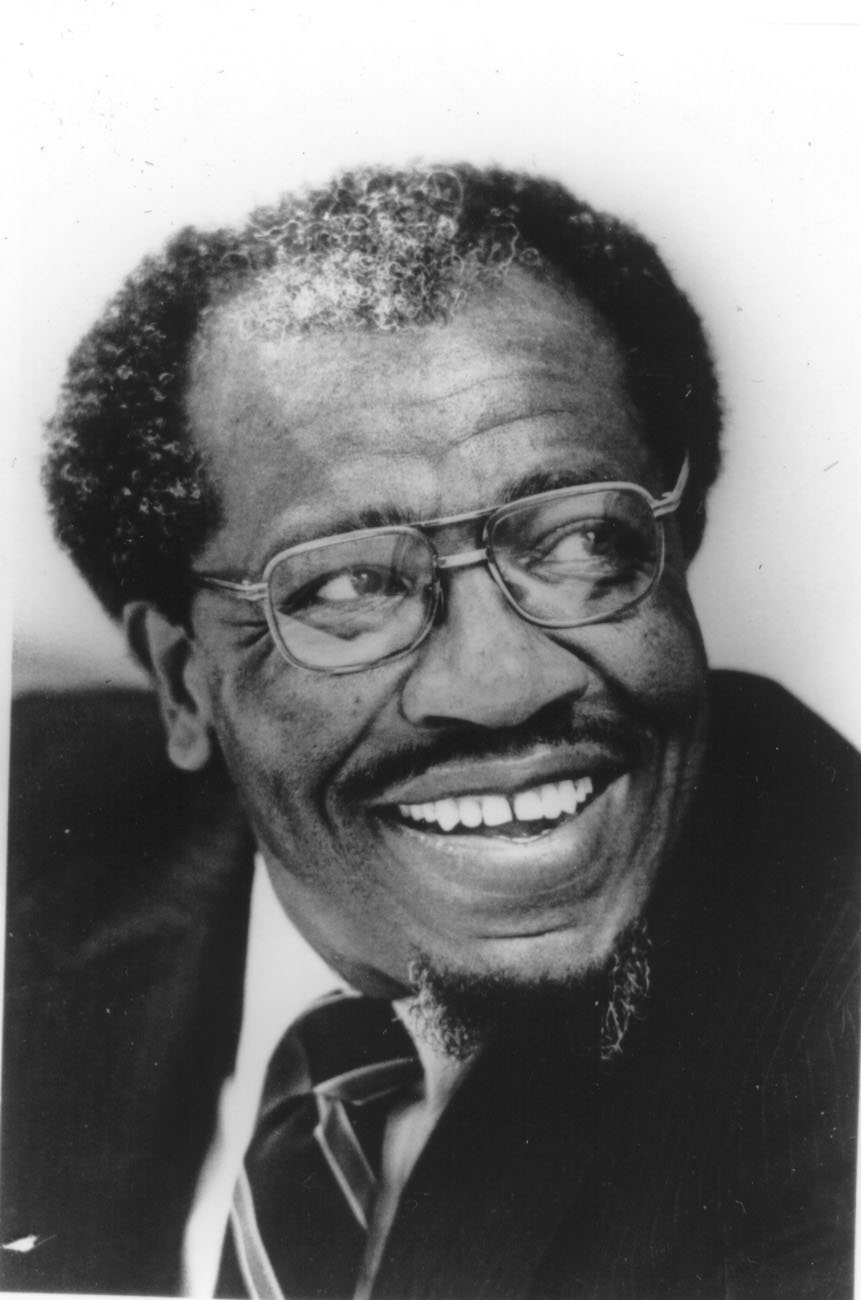

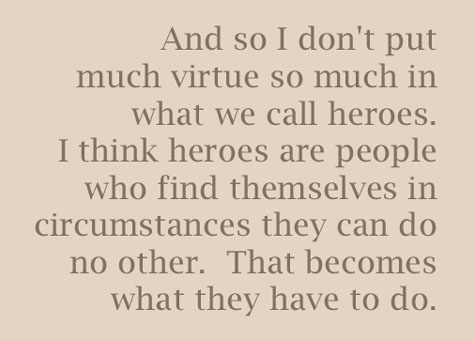

This morning we are looking at the lives and stories of several people through the lens of courage. How do you tend to think about courage? For myself, I think I see it as too rare, either as something which suddenly coalesces, BOOM!, you're doing the courageous thing, or as something I'm not likely to exhibit even if ever given the chance. John Perkins' life gives us a different view of courage, maybe a more everyday view even if it had its more momentous manifestations. Perkins has remarked, "I don't put much virtue in what we call heroes. I think heroes are people who find themselves in circumstances, they can do no other. That becomes what they have to do." So I've titled my presentation "Could He Have Turned Back?" |

|

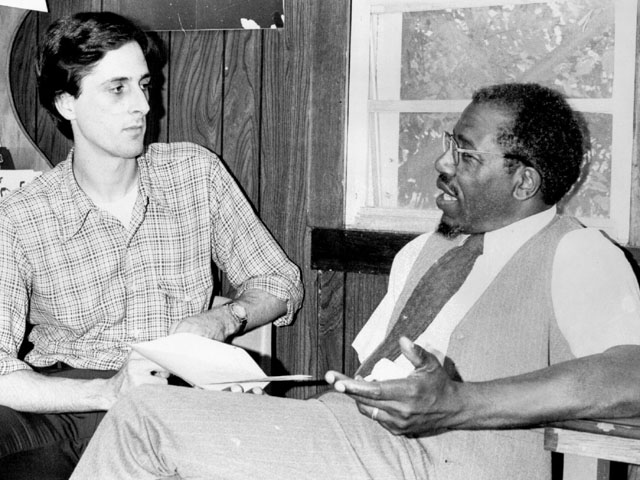

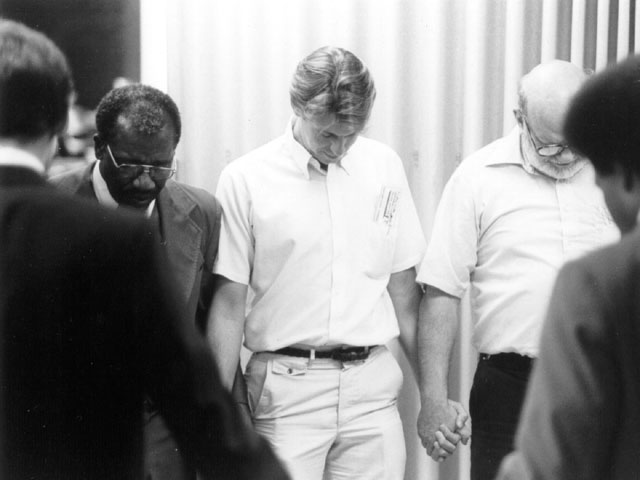

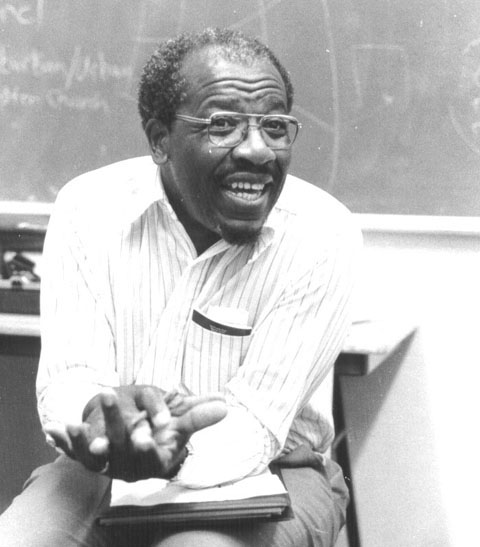

One of the ways we in the Graham Center Archives help preserve the story of

evangelism and missions is by conducting oral histories where people tell us

their story, describing their early life, conversion, evangelistic outreach

or missionary work, and the context in which all that occurred. I did that with

Perkins in June 1987, where I asked him questions and he unfolded his story.

There are many different ways to approach the task of retelling a story like

this. I'm going to do that through the vehicle of excerpts from that interview

with Perkins to tell his story. In preparing for this presentation, I've had

the chance to listen again to the interview I did him. What still impresses

me is his resilience in the context of difficulties and his sense of purpose

and integrity.

One of the ways we in the Graham Center Archives help preserve the story of

evangelism and missions is by conducting oral histories where people tell us

their story, describing their early life, conversion, evangelistic outreach

or missionary work, and the context in which all that occurred. I did that with

Perkins in June 1987, where I asked him questions and he unfolded his story.

There are many different ways to approach the task of retelling a story like

this. I'm going to do that through the vehicle of excerpts from that interview

with Perkins to tell his story. In preparing for this presentation, I've had

the chance to listen again to the interview I did him. What still impresses

me is his resilience in the context of difficulties and his sense of purpose

and integrity.

The outline of Perkins' life, ministry and influence is perhaps well known, and so I will only sketch it out briefly, letting Perkins' own comments from his oral history do some of the story telling to illustrate the world he grew up in and then helped shape. The American South is a major character in the story, but the point is not to beat up on Southerners since the sin of racism is a human rather than regional problem.

Perkins was born in 1930 and grew up on a plantation in rural Mississippi. His mother died before his first birthday and he was raised by his paternal grandmother. Within the web of his cousins and uncles he contributed to the family's gambling and bootlegging enterprise. Listen to these two excerpts as he remembers the signals he was getting from the world around him.

He then talked about resisting this racist system, rebelling against the injustice he lived in the center of, even rebelling against the ease with which he and his family exploited their white customers: |

| PERKINS: Inwardly we rebelled against, as I said, that exploitation of how we exploited people and why we would exploit people. I think we rebelled against that. We also revel...belled against other people that were trying to exploit us. And we'd think that was the most difficult thing. I mean, that was the hardest thing. I think people who tried to take advantage of us was met with strong resistance from...from us. [Pauses] I remember that Jimmy and I went on a strike [laughs]. I m...'member two times as a...as a...as a...you know, we didn't know anything about unions. But I remember one time we was cutting paper wood for a guy, and we realized what he was getting for the paper wood and what we was getting for cutting it, and that...and we demanded...in fact, we tried to demand more and he actually fired us [laughs]. He actually fired us. |

Paper wood, in case you're wondering, is lumber cut to be processed into paper.

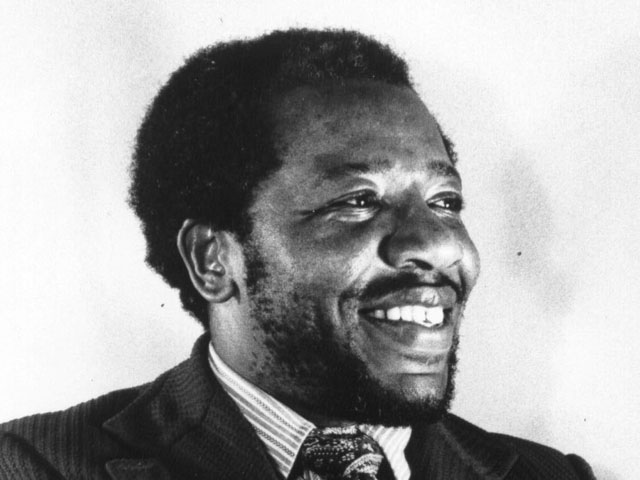

Perkins

grew up, and as a seventeen year old he left to start over in California in

1947 after his brother was killed by a local policeman. He was drafted into

the Army in 1951. After serving in Okinawa, he returned to California, which

became the place where Perkins encountered Jesus in 1957. Perkins himself says

he was looking for love and affirmation, and he found a shadow of it in the

company he worked for whose approval brought some security to him. But Perkins

contrasts this security with the impact of encountering God's love for him:

Perkins

grew up, and as a seventeen year old he left to start over in California in

1947 after his brother was killed by a local policeman. He was drafted into

the Army in 1951. After serving in Okinawa, he returned to California, which

became the place where Perkins encountered Jesus in 1957. Perkins himself says

he was looking for love and affirmation, and he found a shadow of it in the

company he worked for whose approval brought some security to him. But Perkins

contrasts this security with the impact of encountering God's love for him:

PERKINS:

I think I found that love in Christ. I...I think the Gospel [pauses] was the

love of God made visible to me in the sense that I realized that God loved me.

I realized I was loved by God. And if a God in heaven loves me, and if this

God who is creator and Lord of the universe love me, then I'm loved by a very significant

person. I'm...and...and that that person who loves me that much [pauses] loves

me enough to be concerned about my well being. I think I would have thought

of love before I was converted as being [pauses] if my company loved me, if

I worked hard to be loved by my company, then I realized that my country...my

company would...would give me the security I needed in life. And so my love

meant my security. Okay? I understood that. And I think when I recognized and

transferred that to God, that gave me a lot of security.

PERKINS:

I think I found that love in Christ. I...I think the Gospel [pauses] was the

love of God made visible to me in the sense that I realized that God loved me.

I realized I was loved by God. And if a God in heaven loves me, and if this

God who is creator and Lord of the universe love me, then I'm loved by a very significant

person. I'm...and...and that that person who loves me that much [pauses] loves

me enough to be concerned about my well being. I think I would have thought

of love before I was converted as being [pauses] if my company loved me, if

I worked hard to be loved by my company, then I realized that my country...my

company would...would give me the security I needed in life. And so my love

meant my security. Okay? I understood that. And I think when I recognized and

transferred that to God, that gave me a lot of security.

| As Perkins grew as a young Christian, he shared that faith with others. He immediately became involved in a program to share the gospel with children, was instrumental in forming the Fisherman's Gospel Crusade, and joined an outreach to juveniles in prison. A return visit to Mississippi served to generate the conviction to leave California, and overruling the objections of his wife Vera Mae, the family returned to Mississippi in 1960. This clearly was a pivotal choice in Perkins' life. He was leaving the satisfaction and security of a settled life to return to what he had tried to put behind him. How did he feel about returning to Mississippi? |  |

Listening to him tell it in this next excerpt, you can almost overlook that he could have easily and understandably chosen to stay put in California.

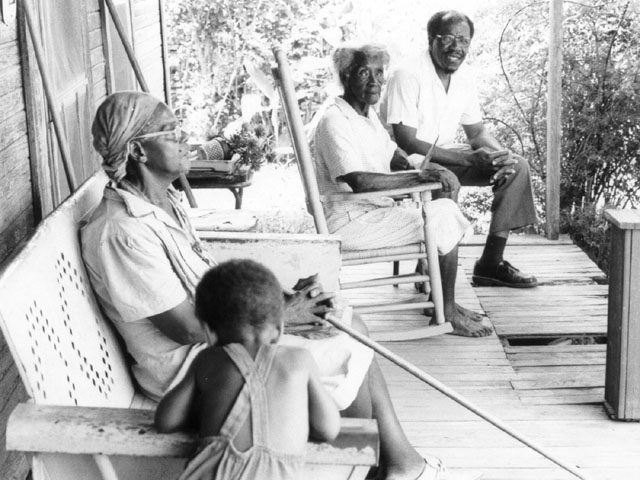

| What he found when he returned to Mississippi was more than the deprivation and abuse and discrimination he had left. He found families and students and marriages and growing children (including his own) and the elderly, whose needs defied being compartmentalized. He saw the spiritual component running through the lives and circumstances of all of these. He came wanting to share his faith but as he lived in and became part of the community, he created a Voice of Calvary Ministries which reconfigured the lines between evangelism and social involvement. |  |

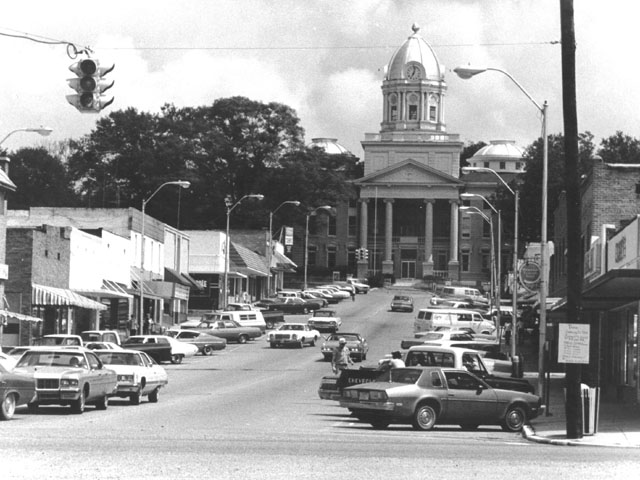

| What emerged from his determination and passion was a proliferation of ministries in the 1960s. As soon as he got to Mississippi, he and Vera Mae began summer Bible classes for community children and then during the school year held them in the are public schools. After relocating from his hometown of New Hebron to nearby Mendenhall, they launched more Bible classes, as well as Sunday schools and Youth for Christ meetings, and evangelistic tent meetings for the whole community. Other programs sprouted: Voice of Calvary Bible Institute, educational opportunities for young people, the Berean Bible Church, a child care center that later became a part of the Head Start program, the registration of area black voters, the Leadership Development Program, and the Federation of Southern Co-ops, which was followed by a housing co-op, farmers' co-op, and a cooperative store. In 1967 the Perkinses participated in the struggle against segregated schools in Mississippi by sending two of their children as the first black students to enroll in Mendenhall's previously all-white public high school. |

|

|

A second pivotal moment in Perkins' life came in late-1969 in Mendenhall. As Perkins says in his book, Let Justice Roll Down, "Ever since blacks had started agitating in the early '60s, white hatred had been rising and rising. Now it was finally spilling over, like water breaking through a dam." (Justice: 135) When he and a few others were arrested and held without charges, he launched a boycott of white Mendenhall businesses during the Christmas shopping season. He was released but two months later in February 1970, Perkins and other picketers were arrested and the beating he received in jail almost ended his life. He was released and recovered, but this kind of beating takes more than physical mending. Seeing no bitterness as I interviewed him, I asked whether he forgave quickly. |

|

Perkins relocated to Jackson, where he resumed his many-pronged ministry and began to explore the implications of what was a developing philosophy of ministry, this time in an urban context. Educational programs, home renovation, community advocacy, a medical clinic, and more. But his tackling social problems and human needs never sidelined his commitment to the gospel. In this excerpt Perkins talks about arriving at a meeting of local leaders to plan for for Billy Graham's upcoming 1975 crusade in Jackson. |

|

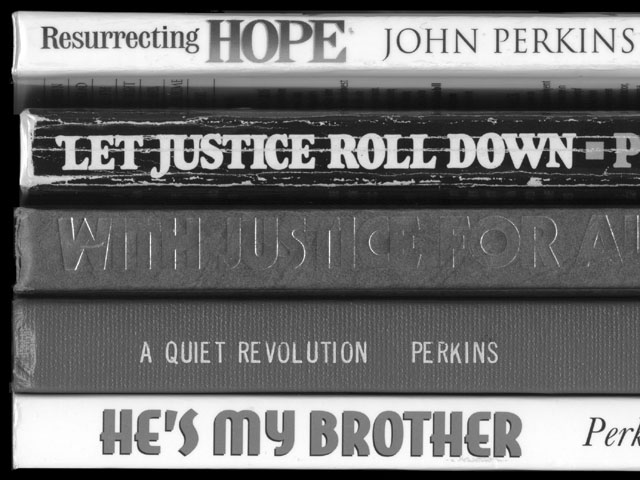

All throughout this time and since, Perkins was speaking locally and around the country, writing books and articles, and serving on the boards of other Christian ministries. The ministry model he formulated, which has been implemented by others throughout the country, can be summed up as the Three Rs: Relocation, Reconciliation and Redistribution. |

| Perkins still serves in areas of need in black and white communities, while also challenging and collaborating with white Christians and churches to extend the reach of his dream. |  |

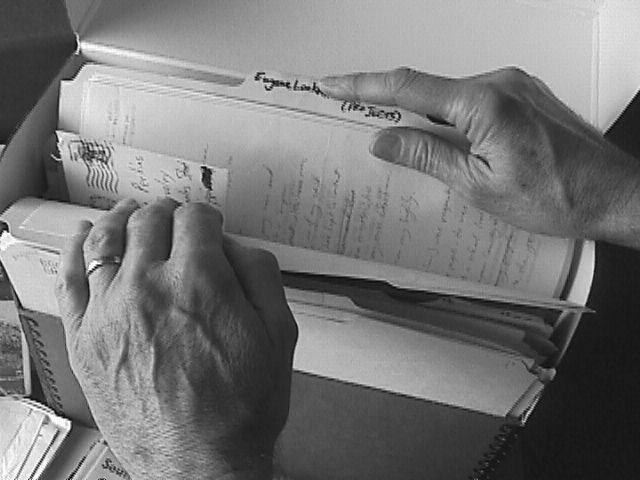

Our purpose this morning isn't simply to isolate and memorialize three contributors to the growth of God's Kingdom. These are three people whose stories are told in the documents in our collections here at the College and we are honored to be stewards of them. If you come to our archives, you can read letters or listen to audio tapes or study photographs which these three created or gathered which now help tell their story. You don't have to just take it from us. You don't have to settle just for the few bits we have had the time to share with you this morning. It is from our larger collections that we are sharing these treasures this morning. The entire John Perkins interview is available on our Web site as both audio files and transcripts. You will find a handout at the back which includes our home page and a brief description of the Perkins collection, and this presentation will be available there in the next several days. |

|

|

Perkins is the one of our three featured figures who is still living. He continues to speak, sharing his dream. He doesn't persuade everyone, but hope leaves those things to God. I suggest that it was in the forge of these circumstances that Perkins' character was not only made but revealed. We see pieces of it being cultivated as he grew up among grandparents, his cousins and uncles and aunts. It received new life as he chose the way of Christian faith and discipleship. And it was cultivated further as he lived out his faith in the context of the Voice of Calvary community and the great needs around him in Mississippi. |

| What we see is the humble and hopeful character which rings true and stirs in us the awareness of what God can accomplish in a person who cares little for their own safety or reputation. Maybe to our surprise Perkins doesn't characterize what he has done as remarkable or a great credit to him. The circumstances, the love of God in his heart, and his convictions allowed him no other choice. And so he returned to the Mississippi he had run from, he led the boycott in Mendenhall, and helped contribute to the ongoing transformation of American Christianity. Let's hear him one last time as he sums up the activity of his life. |  |

|

PERKINS: And so I don't put much virtue in...in...so much in what we call heroes. I think heroes are people who find themselves in circumstances they can do no other. That becomes what they have to do. And so [pauses] they...I think that [pauses]...I think if I'd been killed in the Brandon jail, I would have been forgotten. |